This is the first in a series of posts on the armv1. The full list of posts is:

Ken Shirriff has also written a series of ARM posts arm internals

here.

I really enjoyed reading Ken Shirriff's blogs about reverse engineering the 8085, (e.g.

Inside the ALU of the 8085 microprocessor), and immediately thought of his articles when I saw that the guys over at visual6502.org

announced that they had released the mask level details and full simulation of the very first arm chip - the armv1.

With that in mind I embarked on my own attempt to reverse-engineer parts of the armv1. Some background knowledge of the processor's architecture is helpful, and googling for "ARM Architecture Reference Manual" will lead you to very detailed descriptions of the more modern versions of the processor. By just looking at the masks and knowing a little about the processor's architecture it's possible to make some good guesses at what some of the blocks are.

The barrel shifter is especially obvious when you go to the interactive

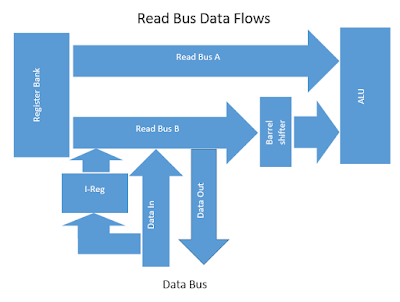

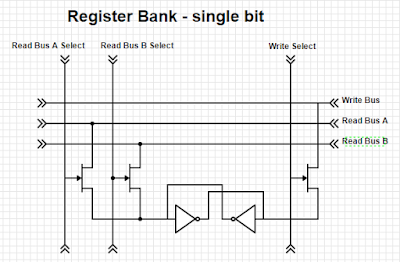

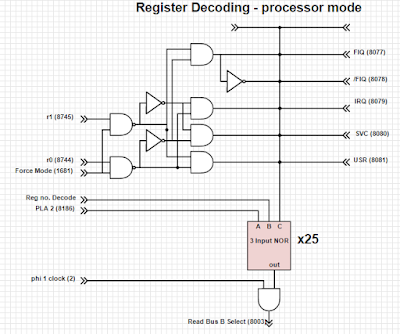

visual6502.org website and zoom in on that portion of the chip and see the diagonal traces. Also, from the architecture description, we know each data-processing (ALU or arithmetic logic unit) instruction selects 3 registers: one destination register (where the ALU result goes), and a register for each of the two operands - Operand 1 and Operand 2. It is therefore a reasonable guess that the Register file has 3 sets of register selection logic, which is verified by the 3 layers of gates of very similar pattern directly above the Register file.

From the architecture description we know that ALU is controlled by 16x opcodes:

So my first step was to ensure I'd found the right area for the ALU. From the architecture description I know that the two inputs to the ALU are:

- Operand 1: the content of register n, as selected by the Rn field of the instruction.

- Operand 2: the output of the barrel shifter (most operations select a shift of 0).

I therefore started by reverse-engineering the barrel-shifter and identifying the barrel-shifter's output. By following the output I knew it would lead to the ALU.

The steps I took to reverse-engineer the ALU were to identify each of the transistors and how they are connected (using the netlists on the

visual6502.org website), converting these into gate circuits, translating these into a schematic, and finally verifying I had captured it correctly by cross checking the simulator's output against the circuit in the schematic.

The portion of the die associated with a single bit slice of the ALU is here:

An example of the translation of transistors into a gate (which corresponds to the upper left circuit of the ALU) is as follows:

The full ALU circuit contains 70+ transistors for each of the 32 bits, or over 2,200 transistors in total.

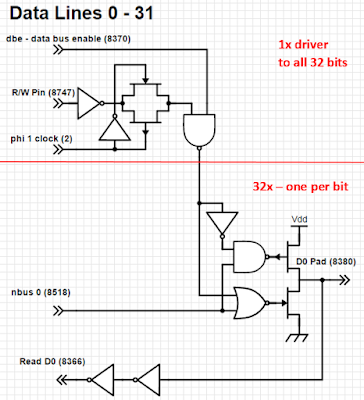

This diagram corresponds to a single bit in the ALU, so this is replicated 32 times to form the full ALU. On the physical silicon these are stacked one on top of the other, although physically the circuit is swapped left for right, as the inputs to the ALU are from the right-hand-side and exit on the left-hand-side.

In the schematic above the control signals (7500, 2370, etc. - these are their net numbers) are shown coming into the circuit from above and below; on the physical silicon all these control signals originate from above the ALU.

The eagle-eyed will also notice that the Carry propagation and Zero calculation circuits alternates slightly between each bit, with b0, b2, etc identical, and b1, b3, etc. identical. The end result is the same but the reason for the difference is to keep the execution path as fast as possible by eliminating an inverter per bit; note that the Carry Out and Zero Out signals are opposite polarity to the inputs.

The 16x different ALU operations are selected by the appropriate setting of the control signals as shown in the table below.

The schematic and the table above give a huge amount of detail! However it can be broken down into smaller, more digestible pieces.

First, note that 2370, 2371, 7484, and 7485 all have the same setting for each opcode; they, and the associated FET transistor isolation circuitry, can be ignored (their purpose is for another discussion).

Second, note that 7393 is only high when it's an arithmetic operation - it purpose is to enable/disable the Carry chain.

Third, Control signal 7500, and the 3x gates at the top left of the schematic, determine whether Operand 1 is inverted on entry to the rest of the ALU (note that the input signal is already inverted, so the 'normal' setting is for it to be 1 to invert it again).

Fourth, control signals 7489 and 7499 select whether Op 2, or its inverted version, is selected through the upper path and to point (A) marked on the schematic.

Similarly, control signals 7487 and 7488 select whether Op 2, or its inverted version, is selected through the lower path and generates signal (B) on the schematic.

The instructions that require a subtraction - sub (subtract), rsb (reverse subtract), and cmp (compare) - do so by converting the associated operand into its twos-complement form by inverting all the bits and adding 1 by feeding a '1' into bit 0 of the carry chain (7326) and then performing an add operation.

The various logic operations (and, or, exclusive or, and bit clear) are selected by selecting the appropriate polarity of each input operand and choosing the right combination of 7489, 7499 and 7487, 7488. For example, note that the only difference in the control signals between the 'and' opcode and 'bic' opcode (bit clear), is that the values on 7489 and 7499 are swapped causing the inverted form of Operand 2 to be fed into the upper calculation path. This is while both 7487 and 7488 are forced high causing signal (B) to be low irrespective of the input.

The table below shows for all of the opcodes some of the intermediate results, and the outputs for one combination of input bits.

So how are the control signals generated? They're created by PLA-1, but how that part of the circuit works is for another day.